Could the Music City Loop Help Propel Nashville Toward a Future Summer Olympics?

As Nashville grows into one of America’s most dynamic cities, long-range infrastructure conversations are expanding to consider what the region could support decades from now. Among the most intriguing possibilities is how the proposed Music City Loop could enable global-scale events while leaving behind one of the nation’s most advanced underground transportation networks. [Read more ➝]

By the LOOP Nashville Editorial Staff

2/16/20266 min read

Cities rarely build transformative infrastructure without a defining reason. Throughout modern history, global events have often provided that catalyst. From Barcelona’s waterfront revival to London’s eastward expansion, the Summer Olympic Games have repeatedly accelerated projects that reshaped urban life for generations.

In Nashville, a city already experiencing remarkable economic and population growth, conversations about long-term infrastructure increasingly revolve around scale—how large the region may become, how people will move efficiently across it, and what investments today could support tomorrow’s demands.

Within that broader context, the proposed Music City Loop from The Boring Company introduces a compelling idea: that a tunneled mobility network could dramatically expand Nashville’s future capacity. When planners and civic observers evaluate the kind of infrastructure capable of supporting the world’s largest sporting event, they are ultimately assessing something deeper than a single moment. They are examining whether a city is building toward global readiness.

And increasingly, Nashville appears to be assembling the physical ingredients of a modern event city.

The Athens of the South Meets the Olympic Tradition

Few American nicknames resonate with Olympic symbolism quite like Nashville’s longstanding identity as the “Athens of the South.” The title reflects the city’s early dedication to higher education and cultural life, but its most visible expression stands proudly inside Centennial Park — a full-scale replica of the ancient Greek Parthenon.

The symbolic connection is difficult to ignore. The original Olympic Games were born in ancient Greece, and cities that embrace public space often find those environments become the emotional heart of the modern Games.

Large parks regularly host fan festivals, international pavilions, medal celebrations, broadcast stages, and cultural programming. Centennial Park’s central geography — minutes from Midtown, major universities, and dense hotel corridors — positions it as a natural gathering place capable of welcoming hundreds of thousands of visitors over the course of an Olympic fortnight.

Yet the park’s potential extends beyond symbolism.

The Centennial Sportsplex, located adjacent to Centennial Park, presents a strong opportunity to expand an existing Olympic-size pool into a world-class aquatics complex. Such an investment would not only support elite competition but also enhance long-term recreational access for residents, aligning with modern planning priorities that emphasize lasting community benefit.

A Downtown Core Built for Major Events

Perhaps the most surprising aspect of evaluating Nashville through an Olympic lens is how much of the necessary venue infrastructure already exists.

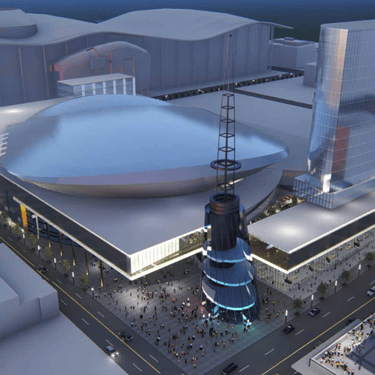

At the forefront is Nissan Stadium, rising along the East Bank as one of the most significant construction projects in city history.

Expected to open in 2027, the enclosed stadium aligns closely with what global event planners seek: modern broadcast infrastructure, weather protection, premium seating environments, and flexible interior space.

An Olympic stadium traditionally hosts opening and closing ceremonies while serving as the athletics venue — the centerpiece of the Games. Constructing such a facility from scratch is often the single largest expense for host cities. Nashville’s decision to build one regardless dramatically lowers the conceptual barrier to hosting global-scale events.

Just as important is its location within the rapidly evolving East Bank district, an area widely expected to accommodate significant mixed-use growth in the coming decades.

A short distance across the river sits Bridgestone Arena, long recognized as one of the nation’s busiest arenas.

Facilities of this scale routinely host Olympic basketball, gymnastics, wrestling, volleyball, and handball. Its integration into downtown’s entertainment district offers a powerful advantage: walkability.

Modern Olympic strategy emphasizes tight venue clustering to reduce transportation strain. When spectators can move between hotels, restaurants, fan zones, and competition sites largely on foot, operational complexity drops significantly.

Nearby, Music City Center provides one of Nashville’s most strategically valuable — if less publicly celebrated — assets.

Convention centers frequently transform into multi-sport environments during the Olympics, hosting fencing, judo, taekwondo, boxing, table tennis, and weightlifting. Just as critically, they house the International Broadcast Centre and Main Press Centre, which together support the massive global media operation transmitting the Games worldwide.

Quietly, facilities like this form the logistical backbone of the Olympics.

Taken together, the stadium, arena, and convention center outline a dense urban competition zone — precisely the configuration international planners prefer.

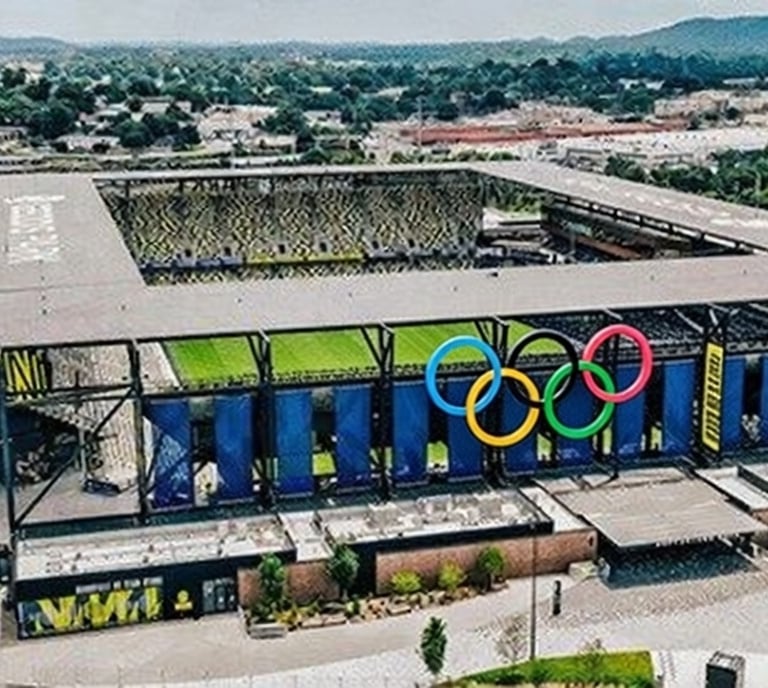

Soccer Already Solved

Many cities must construct or heavily retrofit stadiums to support Olympic soccer. Nashville begins from a position of strength thanks to GEODIS Park.

Purpose-built for top-tier soccer, the stadium simplifies tournament logistics while delivering an exceptional spectator experience. Olympic soccer unfolds across multiple venues, meaning GEODIS Park could immediately anchor match scheduling.

The venue’s rectangular geometry also makes it an excellent candidate for rugby sevens — one of the Olympics’ fastest-growing sports.

Meanwhile, Vanderbilt Stadium offers valuable secondary capacity.

Secondary stadiums rarely command headlines, yet they are indispensable to Olympic scheduling. Early-round matches require high-quality venues without overwhelming primary facilities. Vanderbilt’s Midtown location also places it near hotels and medical centers — both critical during global events.

Even First Horizon Park presents noteworthy flexibility.

If baseball appears on a future Olympic program, the ballpark could host preliminary games. Its shape also lends itself to temporary conversion for archery, a discipline often staged in adapted venues with clear sightlines.

Collectively, these facilities suggest Nashville already possesses a venue ecosystem far stronger than many might assume.

Aquatics and the Opportunity for Civic Legacy

Swimming is among the most watched Olympic sports, and aquatics venues are technically demanding.

Centennial Sportsplex currently serves as a valued community resource, yet transforming it into an Olympic-scale venue would likely require a full rebuild rather than retrofit.

Modern Olympic aquatics centers require expansive deck space, high roof clearance for broadcast lighting, and seating often exceeding 15,000 spectators.

Constructing a new facility near Centennial Park would align event readiness with long-term public benefit — expanding swim access, supporting youth athletics, and strengthening Nashville’s recreation infrastructure.

Legacy planning increasingly defines successful Olympic hosts, and projects that enhance daily life tend to earn the strongest civic support.

A Natural Stage for Rowing

Beyond the urban core, J. Percy Priest Lake stands out as a compelling venue candidate for rowing and canoe sprint competitions.

Olympic rowing demands long, straight stretches of protected water with minimal current — conditions typically easier to achieve on lakes.

Preliminary assessments suggest portions of Percy Priest could support the standard 2,000-meter course, while surrounding parkland could accommodate temporary grandstands without extensive permanent construction.

Such strategies are increasingly favored, allowing cities to host world-class events without overbuilding infrastructure.

Transit as the Transformational Layer

If venues represent Nashville’s quiet strength, mobility remains the element most capable of reshaping the city’s long-term potential.

Mega-events require transportation systems that move large crowds predictably. Reliability matters as much as raw capacity.

This is where the Music City Loop introduces a transformative possibility.

Inspired in part by systems like the Las Vegas Convention Center Loop, a tunneled network could connect the airport, downtown, the East Bank, Midtown, and major venue clusters while bypassing surface congestion entirely.

Predictable travel times protect broadcast schedules, support athlete preparation, and enhance the spectator experience. Just as importantly, underground transit compresses geography — making destinations feel closer and more integrated.

Winning an Olympic bid would also create powerful economic alignment for rapid network expansion. Global events operate on fixed timelines, and host cities must deliver infrastructure before the opening ceremony. Under those conditions, it would make strong business sense for The Boring Company to accelerate construction and build the Loop at scale, establishing high-capacity corridors far faster than traditional timelines might allow.

Mega-events often unlock both public and private investment simultaneously, enabling transportation networks to mature in years rather than decades.

The Legacy Beneath the Streets

Perhaps the most compelling aspect of viewing Nashville through this lens is what would remain afterward.

A Loop system designed for global demand could leave behind one of the most advanced underground mobility networks in the United States — improving airport access, strengthening cross-town connectivity, and supporting continued economic expansion.

Planning transit at Olympic scale would not mean building infrastructure solely for a few weeks of competition. Instead, it would establish a durable transportation framework capable of adapting alongside Nashville’s growth.

Shorter commutes, more reliable travel times, and expanded neighborhood connections would benefit residents long after the world’s attention moved on.

In this way, the Olympic framework becomes less about spectacle and more about acceleration — a mechanism that brings forward infrastructure investments destined to shape the city anyway.

Expanding Nashville’s Horizon

Exploring Nashville through the lens of a future Olympic host reveals something deeper than event readiness. It highlights a city entering a new phase of confidence.

From the symbolic presence of Centennial Park to an expanding inventory of world-class venues, the structural foundation of a modern event city is increasingly visible. Add a transportation system capable of delivering predictable mobility beneath the streets, and the realm of possibility expands.

Whether Nashville ever seeks the Games remains a question for the future. What is clear today is that investments in connectivity, recreation, and civic infrastructure are positioning the city for opportunities once reserved for much larger metros.

In that sense, the Music City Loop represents more than a transportation concept.

It reflects a growing belief in Nashville’s trajectory — and the understanding that infrastructure built with vision has the power to redefine what a city can become.

Disclaimer

LOOP Nashville aggregates publicly available news, commentary, and editorial content related to the Music City LOOP project. All source material is fully credited and attributed to its original publishers. All commentary and editorial opinions are solely those of the LOOP Nashville Editorial Staff. We are an independent site and are not affiliated with The Boring Company or the Music City LOOP project.

CONTACT

Follow

scoop@loopnashville.com

© 2025. All rights reserved.