Three Pathways Across the Cumberland: How the Music City Loop Could Reach the East Bank

With new reports suggesting the Loop may extend beneath Broadway and West End, Nashville now faces a timely question: should the Cumberland River be part of the alignment? Three crossing concepts have emerged—and each carries its own technical and civic considerations. [Read more ➝]

By the LOOP Nashville Editorial Staff

11/21/20254 min read

A Moment of Opportunity for Routing Decisions

Recent reporting has indicated that the Music City Loop is expected to extend beneath Broadway and West End. With that momentum in place, the next question has moved squarely into civic view: should the river be crossed to bring the East Bank into the network? As development accelerates around the new TPAC site, Nissan Stadium, and the broader East Bank master plan, choices made today may determine whether transit can be integrated before the opportunity is lost to structural foundation, utilities, or permanent site layout.

This question is particularly relevant because publicly owned corridors still provide viable tunneling routes that could reach the East Bank. At the same time, private rail right-of-way presents yet another path that could lead to high-value destinations — if collaboration can be secured in time.

Three major crossing concepts now sit at the center of the discussion.

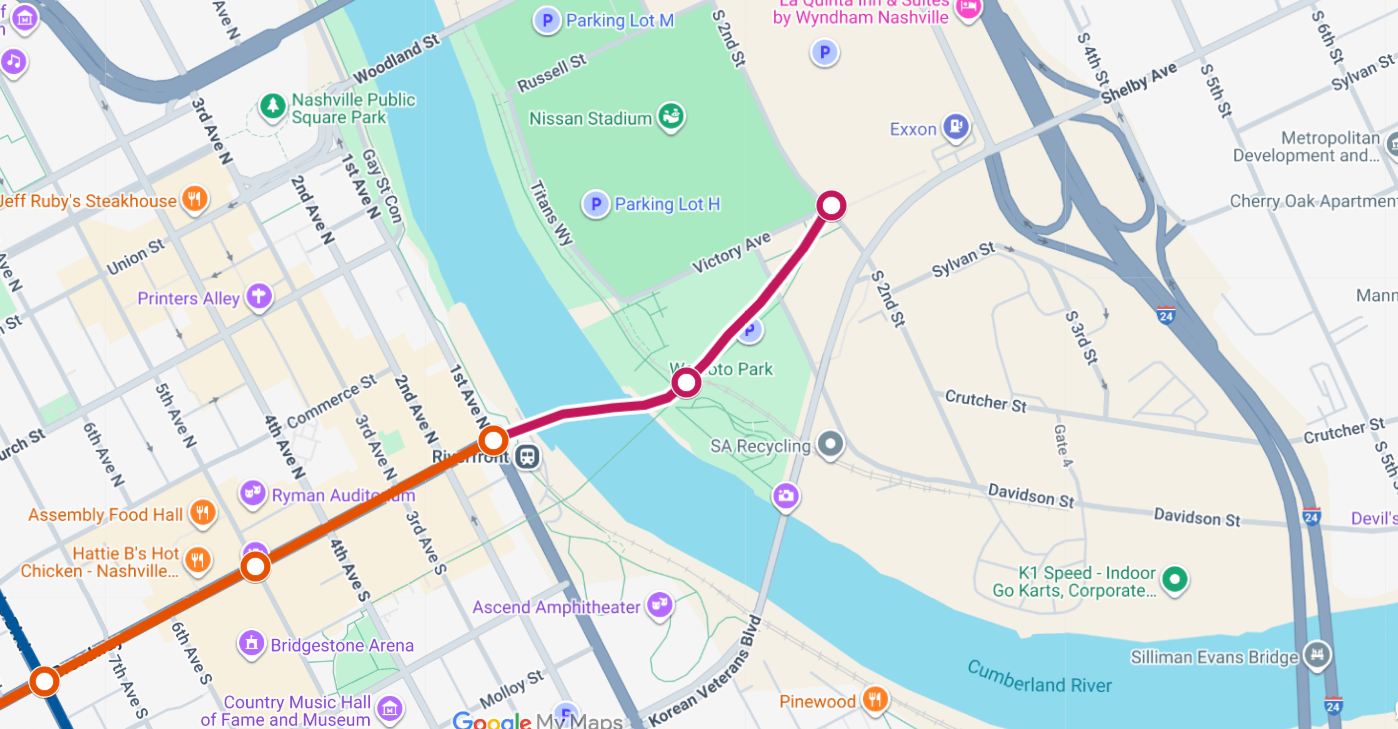

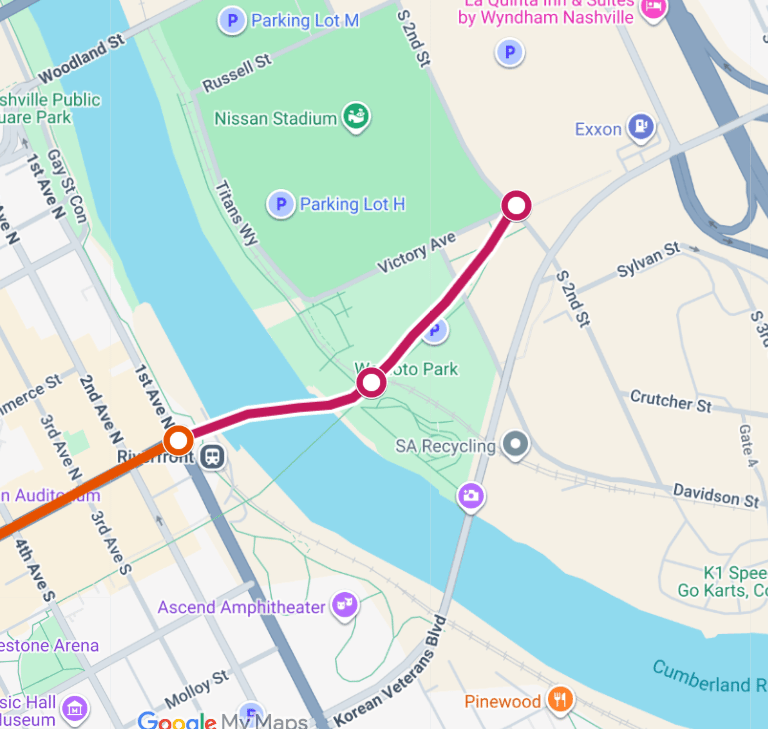

Alignment One: Broadway-to-East Bank — The Most Direct Path

The first alignment would extend the Broadway/West End tunnel eastward directly beneath the Cumberland River to reach both the future TPAC building and the new Nissan Stadium. This is the most straightforward path between major activity hubs and could allow station placements to be integrated into new structures currently being planned.

Such a route would require cooperation with the East Bank Development Authority due to jurisdiction over land beneath and surrounding the TPAC and stadium sites. However, synchronizing transit and construction could allow foundation types, structural clearances, and utility placement to be designed with transit in mind—rather than retrofitted later.

This alignment positions underground transit within walking distance of civic, cultural, and entertainment venues. It is also the closest to existing parking concentrations and future riverfront park space, which could allow for multimodal connections, event-day traffic management, and year-round mobility between downtown and the East Bank.

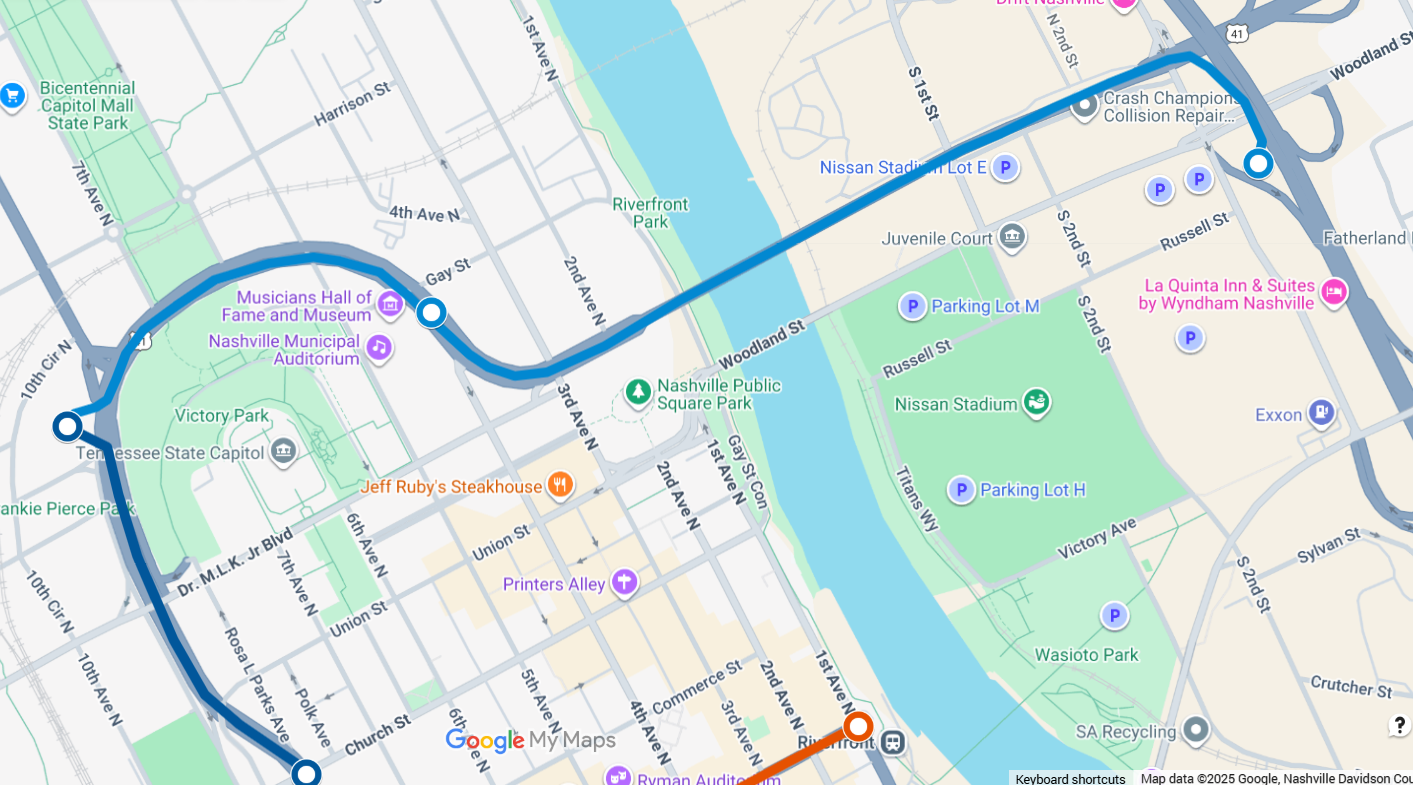

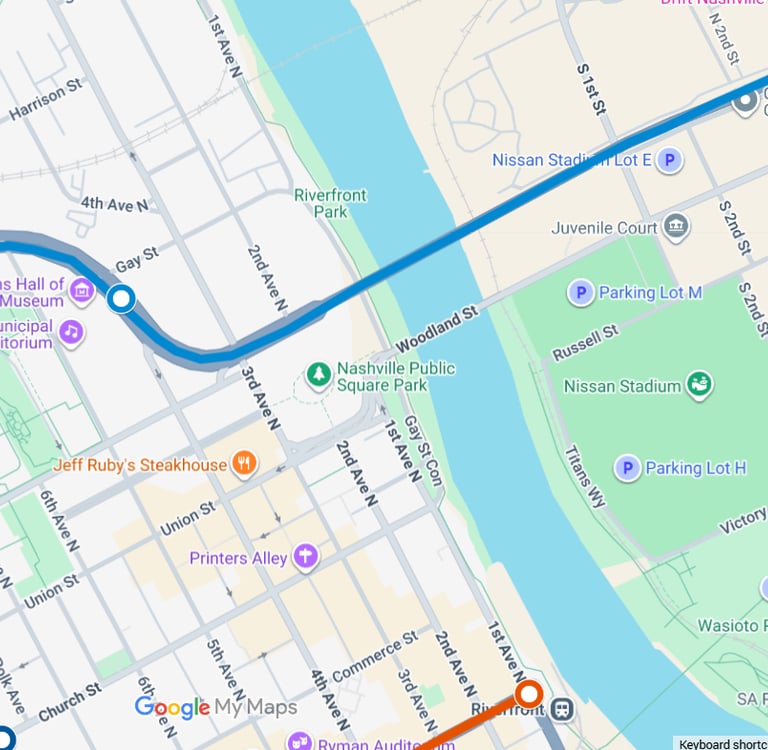

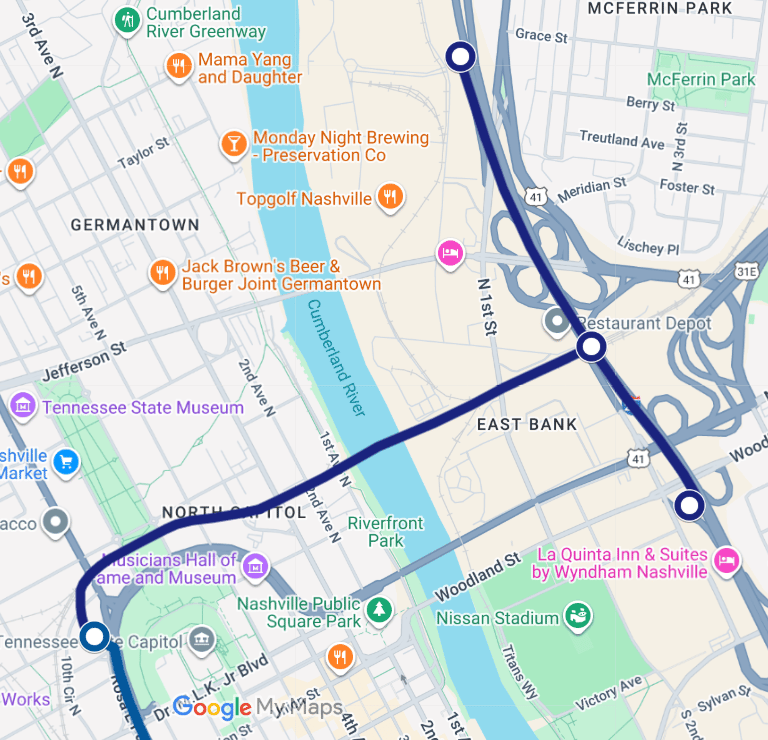

Alignment Two: James Robertson Parkway — A Fully State-Owned Route

A second alignment uses only state-owned property, beginning at the Rosa L. Parks Boulevard station and continuing beneath James Robertson Parkway (U.S. Highway 41) directly toward Nissan Stadium. Because all land in this corridor is already under state control, this route may offer Nashville’s most clear legal pathway for advancing an East Bank crossing.

This alignment would likely require access only to stadium-area parcels and could be advanced without involving the East Bank Development Authority. The routing would also have the added benefit of reaching Nashville Municipal Auditorium — a high-traffic venue with limited nearby parking. Access to a LOOP station could dramatically revitalize the auditorium’s usage by solving what has long been its biggest limitation: a lack of accessible parking within a short walking radius.

While the TPAC site would remain out of reach under this option unless future cooperation was established, the corridor provides a powerful network of destinations. In addition to stadium access, this route uses an existing roadway with long, straight geometry that simplifies underground construction while remaining entirely within state ownership.

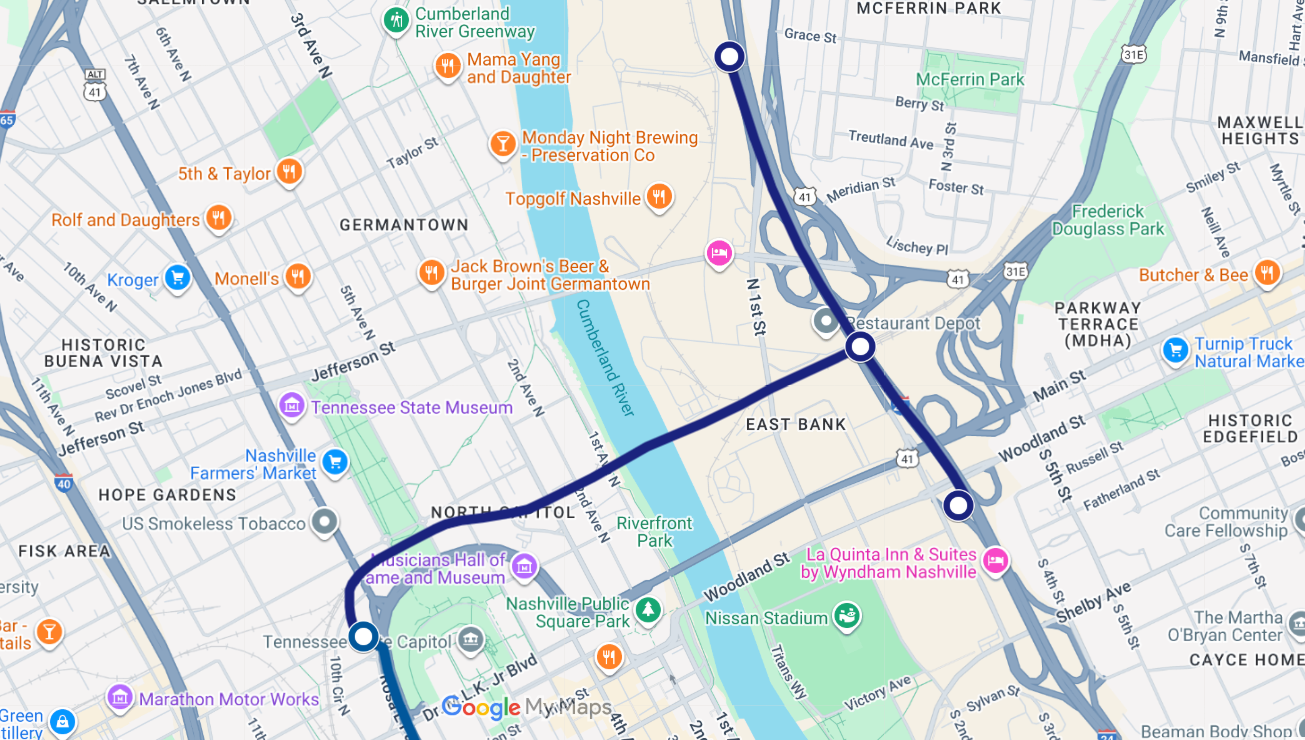

Alignment Three: CSX Rail Corridor and State Property Intersections

A third option examines whether coordination between CSX and the State of Tennessee could allow the Loop to follow existing rail infrastructure across the Cumberland. Several CSX right-of-way points intersect with state-owned parcels, creating potential handoff locations where a LOOP alignment could shift beneath state land under the Interstate property and approach both Nissan Stadium and the emerging Oracle campus.

This alignment would serve destinations that generate both employment and visitor traffic. It positions the Oracle campus, adjacent hotels, new residential, and stadium districts as consistent ridership generators spread across all hours of the week — different from stadium-only usage and therefore valuable to an economically sustainable transit model.

Although more complex to negotiate, a CSX partnership could allow the LOOP to coexist alongside machinery and logistics already functioning on the industrial edge of downtown. This alternative would not require city or East Bank approval and open a functional corridor between job centers, entertainment venues, and future East Bank development without major changes to the existing urban street grid.

Technical Depth: What Lies Underneath

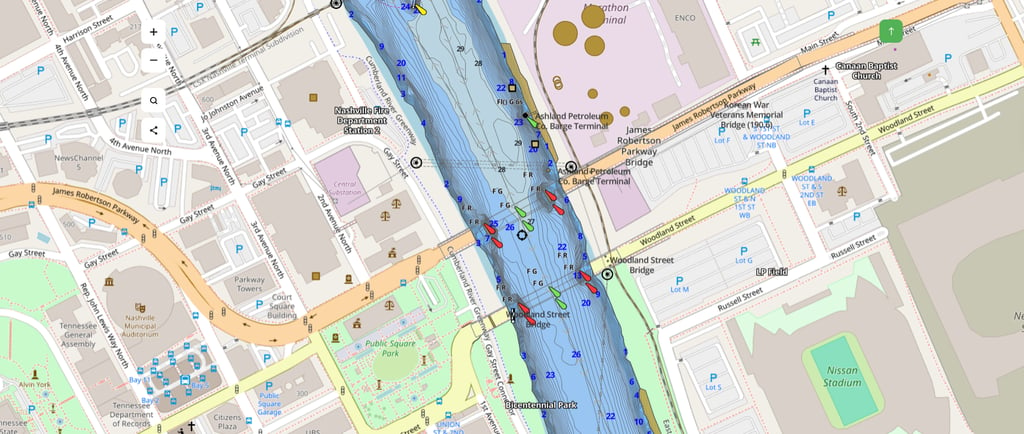

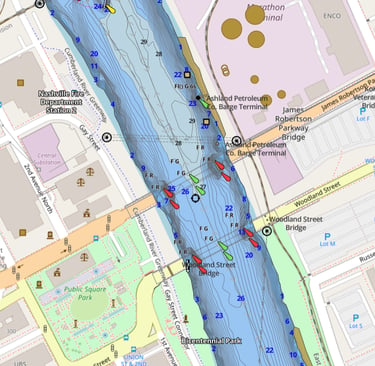

Along all three proposed alignments, the Cumberland River reaches a maximum depth of only 27 feet. While that is shallow by engineering standards, any tunnel would need to pass significantly deeper — likely 60 to 100 feet below the river surface — to remain clear of erosion layers, navigational channels, and future shoreline reinforcement.

The Boring Company’s pressurized tunnel boring systems are designed for precisely these conditions. Their machines operate beneath water tables, handle mixed soils, and regulate internal pressure throughout the bore. Though site-specific surveys will eventually be required, no aspect of the river’s depth currently appears to pose an insurmountable logistical barrier. The engineering techniques needed to cross the river are already in use elsewhere in the United States.

Regional Connectivity: East Nashville, Opryland, and Park-and-Ride Possibilities

If the river is crossed, the implications reach far beyond the stadium district. The East Bank could become a gateway to a larger expansion heading toward East Nashville using Ellington Parkway — another major state-owned transportation corridor. Ellington Parkway’s alignment offers a unique opportunity: it could carry the Loop further northeast beneath land already controlled by the state, avoiding complex property acquisition or local right-of-way conflicts.

This alignment could support park-and-ride facilities on the outer edges of town, giving residents from the suburbs a place to drive, park in structured lots, and then travel downtown via the LOOP — keeping thousands of cars out of the urban core and off the interstates. Ellington Parkway also intersects directly with Briley Parkway, another fully state-owned corridor. That connection would naturally position a future extension toward Opryland Hotel, which has already expressed interest in the LOOP project. The opportunity to link hotels, convention spaces, stadiums, civic venues, and major employers into one internal transit grid could reshape mobility along the entire river corridor.

In this vision, crossing the river is not an endpoint — it is the first step in building a larger network that connects neighborhoods, reduces vehicle congestion, and redefines regional access to the city’s most vital destinations.

Disclaimer

LOOP Nashville aggregates publicly available news, commentary, and editorial content related to the Music City LOOP project. All source material is fully credited and attributed to its original publishers. All commentary and editorial opinions are solely those of the LOOP Nashville Editorial Staff. We are an independent site and are not affiliated with The Boring Company or the Music City LOOP project.

CONTACT

Follow

scoop@loopnashville.com

© 2025. All rights reserved.